Granted, I didn't find her final book that great, it was the story telling of the whole series that made the journey worthwhile.

Three stories here (there were 5, so far, that has been released)... each with their own lessons...

Babbitty Rabbitty and her Cackling Stump

A large tree stump (with twenty growth rings—we counted) squats atop Rowling's fourth and longest fairy tale. Five tentacle-like roots spread from the base with grass and dandelion clocks sprouting out from beneath them. At the center of the base of the stump is a dark crack, with two white circles that look like tiny eyes peering out at the reader. Under the text is a small narrow paw print (with four toes). Not as horrific as the bloody, hairy heart of the last story (and this time we do see bright pixie dust on the facing page), but we don’t entirely like the looks of that stump.

A large tree stump (with twenty growth rings—we counted) squats atop Rowling's fourth and longest fairy tale. Five tentacle-like roots spread from the base with grass and dandelion clocks sprouting out from beneath them. At the center of the base of the stump is a dark crack, with two white circles that look like tiny eyes peering out at the reader. Under the text is a small narrow paw print (with four toes). Not as horrific as the bloody, hairy heart of the last story (and this time we do see bright pixie dust on the facing page), but we don’t entirely like the looks of that stump."Babbitty Rabbitty and her Cackling Stump" begins (as good fairy tales often do) long ago and in a faraway land. A greedy and "foolish king" decides that he wants to keep magic all to himself. But he has two problems: first, he needs to round up all the existing witches and wizards; second, he needs to actually learn magic. Just as he commands a "Brigade of Witch Hunters" armed with a pack of fierce black dogs, he also announces his need for an "Instructor in Magic" (not too bright, our king). Savvy wizards and witches go into hiding rather than heed his call, but a "cunning charlatan" with no magical ability at all bluffs his way into the role with a few simple tricks.

Once installed as the head sorcerer and private instructor to the King, the charlatan demands gold for magical supplies, rubies for creating charms, and silver cups for potions. The charlatan hoards these items in his own house before returning to the palace, but he does not realize the King's old "washer-woman," Babbitty, sees him. She watches him pull twigs from a tree that he then presents to the King as wands. Cunning as he is, the charlatan tells the King that his wand will not work until "your Majesty is worthy of it."

Every day the King and charlatan practice their "magic" (Rowling shines here, painting a portrait of the ridiculous King waving his twig and "shouting nonsense at the sky"), but one morning they hear laughter and see Babbitty watching from her cottage, laughing so hard she can hardly stand. The humiliated King is furious and impatient, and demands that they give a real demonstration of magic in front of his subjects the very next day. The desperate charlatan says it is impossible since he needs to leave the kingdom on a long journey, but the now suspicious King threatens to send the Brigade after him. Having worked himself into a fury, the King also commands that if "anybody laughs at me" the charlatan will be beheaded. And so, our foolish, greedy, magic-less King is also revealed to be both prideful and pitifully insecure--even in these short, simple tales, Rowling is able to create complex, interesting characters.

Looking to "vent" his frustration and anger, the cunning charlatan heads straight to the house of Babbitty. Peering in the window, he sees a "little old lady" sitting at her table cleaning her wand, as the sheets are "washing themselves" in a tub. Seeing her as a real witch, and both the source and solution of his problems, he demands her help, or he will turn her over to the Brigade. It is hard to fully describe this powerful turning point in the story (and any of these tales, really). Try to remember the richness and color of Rowling's novels and imagine how she might pack these bite-sized tales full of vivid imagery and subtle nuances of character.

Unruffled by his demands (she is a witch, after all), Babbitty smiles and agrees to do "anything in her power" to help (there’s a loophole if we’ve ever heard one). The charlatan tells her to hide inside a bush and perform all the spells for the King. Babbitty agrees, but wonders aloud what will happen if the King tries to perform an impossible spell. The charlatan, ever convinced of his own cleverness and the stupidity of others, laughs off her concerns, asserting that Babbitty's magic is certainly much more powerful than anything "that fool's imagination" could dream up.

The next morning, the members of the court gather together to witness the King's magic. From a stage, the King and charlatan perform their first magical act--making a woman's hat disappear. The crowd is amazed and astonished, never guessing that it is Babbitty, hiding in a bush, who performs the spell. For his next feat, the King points the "twig" (every reference of this cracks us up) at his horse, raising it high into the air. Looking around for an even better idea for the third spell, the King is interrupted by the Captain of the Brigade, who holds the body of one of the King's hounds (dead from a poisonous mushroom). He begs the King to bring the dog "back to life," but when the King points the twig at the dog, nothing happens. Babbitty smiles inside her hiding place, not even trying a spell, for she knows "no magic can raise the dead" (at least not in this story). The crowd begins to laugh, suspecting that the first two spells were just tricks. The King is furious, and when he demands to know why the spell failed, the cunning and deceitful charlatan points at Babbitty's hiding place and screams that a "wicked witch" is blocking the spells. Babbitty runs from the bush, and when the Witch Hunters send the hounds after her, she disappears, leaving the dogs "barking and scrabbling" at the base of an old tree. Desperate now, the charlatan shouts that the witch has turned herself "into a crab apple" (which even at this tense and dramatic point draws a snicker). Fearful that Babbitty may turn herself back into a woman and expose him, the charlatan demands the tree be cut down--because that is how you "treat evil witches." It is quite a powerful scene, not only for its "off with her head!" drama, but because the charlatan's ability to whip up the crowd is evocative of the all-too-real witch trials. As the drama builds, Rowling's handwriting appears slightly less polished--the spaces between letters of her words widens, creating the illusion that she's making the story up as she goes along, getting the words down on the page as fast as she can.

The tree is chopped down, but as the crowd cheers and heads back toward the palace, a "loud cackling" is heard, this time from within the stump. Babbitty, smart witch that she is, shouts that witches and wizards cannot be killed by being "cut in half," and to prove it, she suggests that they cut the King's instructor "in two." At this, the charlatan begs for mercy and confesses. He is dragged to the dungeon, but Babbitty is not finished with her foolish king. Her voice, still issuing from the stump, proclaims that his actions have invoked a curse on the kingdom, so that every time the King harms a witch or wizard he too will feel a pain so fierce he will wish to "die of it." The now desperate King falls to his knees and promises to protect all the wizards and witches in his lands, allowing them to perform magic without harm. Pleased, but not completely satisfied, the stump cackles again and demands a statue of Babbitty be placed upon it to remind the King of his "own foolishness." The "shamed King" promises to have a sculptor create a statue in gold, and he heads back to the palace with his court. At last, a "stout old rabbit" with a wand in its teeth hops out from hole beneath the stump (aha! The source of those tiny white eyes) and leaves the kingdom. The golden statue remained on the stump forever more, and witches and wizards were never be hunted in the kingdom again.

"Babbitty Rabbitty and her Cackling Stump" highlights the winking ingenuity of the old witch--who should remind fans of a certain wise and resourceful wizard--and you can imagine how old Babbitty might become a folk hero to young wizards and witches. But more than just a story about the triumph of a clever witch, the tale warns against human weaknesses of greed, arrogance, selfishness and duplicity, and shows how these errant (but not evil) characters come to learn the error of their ways. The fact that the tale follows so soon after that of the mad warlock highlights the importance that Rowling has always placed on self-awareness: Babbitty reveals to the King his arrogance and greed, just as the Hopping Pot exposes the wizard's selfishness and the Fountain uncovers the hidden strength of the three witches and the knight. Of the first four of her tales, only the hairy-hearted warlock suffers a truly horrible fate, as his unforgiveable use of the Dark Arts and his unwillingness to know his true self exclude him from redemption.

The Wizard and the Hopping Pot

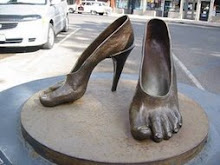

As in her Harry Potter series, garnishing the top of the first page of the first fairy tale, "The Wizard and the Hopping Pot," is a drawing--in this case, a round pot sitting atop a surprisingly well-drawn foot (with five toes, in case you were wondering, and we know some of you were). This tale begins merrily enough, with a "kindly old wizard" whom we meet only briefly, but who reminds us so much of our dear Dumbledore that we must pause and take a breath.

As in her Harry Potter series, garnishing the top of the first page of the first fairy tale, "The Wizard and the Hopping Pot," is a drawing--in this case, a round pot sitting atop a surprisingly well-drawn foot (with five toes, in case you were wondering, and we know some of you were). This tale begins merrily enough, with a "kindly old wizard" whom we meet only briefly, but who reminds us so much of our dear Dumbledore that we must pause and take a breath.This "well-beloved man" uses his magic primarily for the benefit of his neighbors, creating potions and antidotes for them in what he calls his "lucky cooking pot." Much too soon after we meet this kind and generous man, he dies (after living to a "goodly age") and leaves everything to his only son. Unfortunately, the son is nothing like his father (and entirely too much like a Malfoy). Upon his father's death, he discovers the pot, and in it (quite mysteriously) a single slipper and a note from his father that reads, "In the fond hope, my son, that you will never need this." As in most fairy tales, this is the moment when things start to go wrong....

Bitter about not having anything but a pot to his name and completely uninterested in anyone who cannot do magic, the son turns his back on the town, closing his door to his neighbors. First comes the old woman whose granddaughter is plagued with warts. When the son slams the door in her face, he immediately hears a loud clanging in the kitchen. His father's old cooking pot has sprouted a foot as well as a serious case of warts. Funny, and yet gross. Vintage Rowling. None of his spells work, and he cannot escape the hopping, warty pot that follows him--even to his bedside. The next day, the son opens the door to an old man who is missing his donkey. Without its help to carry wares to town, his family will go hungry. The son (who clearly has never read a fairy tale) slams the door on the old man. Sure enough, here comes the warty, befooted clanging pot, now having captured both the sounds of a braying donkey as well as groans of hunger.

In true fairy tale fashion, the son is besieged with more visitors, and it takes a few tears, some vomit, and a whining dog before the wizard at last succumbs to his responsibility, and the true legacy of his father. Renouncing his selfish ways, he calls for all townspeople far and wide to come to him for help. One by one, he cures their ills and in doing so, empties the pot. At the very last, out pops the mysterious slipper--the one that perfectly fits the foot of the now-quiet pot--and together the two walk (and hop) off into the sunset.

Rowling has always made her stories as funny as they are clever, and "The Wizard and the Hopping Pot" is no exception; the image of a one-footed cooking pot plagued with all the "warty" ills of the village, hopping after a selfish young wizard, is a good example. But the real magic of this book and this particular tale lies not just in her turns of phrase but in the way she underlines the "clang, clang, clang" of the pot for emphasis, and how her handwriting gets messier when the story picks up speed, like she's hurrying along with the reader. These touches make the story uniquely her own and this volume of stories particularly special.

The Tale of the Three Brothers

If, like us, you raced through your first reading of "The Tale of the Three Brothers" on your way to the finale of all finales, then you missed quite a tale (one that we think can stand among the best of Aesop). Lucky for you, you can open your copy of Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows to Chapter Twenty-One and read it any time you like.

If, like us, you raced through your first reading of "The Tale of the Three Brothers" on your way to the finale of all finales, then you missed quite a tale (one that we think can stand among the best of Aesop). Lucky for you, you can open your copy of Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows to Chapter Twenty-One and read it any time you like.A trio of toothy skulls stare out at the reader at the top of the last of the five tales (oh how we wish there were dozens more). The skull in the middle has a symbol carved into its forehead--a straight vertical line in a circle, enclosed by a triangle. Underneath the text is a pile of fabric, upon which lies a wand (spouting a swirling stream of sparkles), and what looks like a small stone.

This spooky tale about three brothers, three choices, and three distinct fates begs to be read aloud--in fact, the first time we meet the three brothers is when Hermione reads the tale to Harry and Ron (and Xenophilius). Three brothers traveling along a deserted road at "twilight" (midnight, according to Mrs. Weasley's version of the story) come to a "treacherous" river they cannot cross. Well versed in magic, they create a bridge with a wave of their wands. Halfway across they are halted by a "hooded figure." Death is angry, and tells the brothers (in a funny moment from Hallows, Harry interrupts the story here "Sorry, but Death spoke to them?") that they have cheated him out of "new victims" since people usually drown when they try to cross the river. But, Death is shrewd and offers a reward to each of them for being smart enough to "escape" him. Our favorite fairy tales have this same kind of "choose your fate" plot--you can learn so much about a character from a single choice, and the best stories, like this one, lead you away from where you think it's going toward an ending you never expected.

The oldest brother, a "combative man" asks for the mightiest wand ever created--a wand that will win every duel for its owner, one befitting a wizard who "conquered Death." So Death creates the (fateful) wand from an "Elder tree" (capitalized in our copy) and gives it to the quarrelsome, boastful brother. The second brother, an "arrogant man" who is determined to demean Death further, asks for the power to summon others back from Death. Picking up a stone from the ground, Death tells the brother that it holds the power to bring back the dead. The youngest brother, the most humble and wise of the three, did not "trust Death" so he asks for something to allow him to leave without being "followed by Death." Knowing he may have been outsmarted, Death, hands over "his own" invisibility cloak with a "very bad grace". Each brother's choice reveals so much about his motivations: the oldest brother wants the Elder wand to make him powerful over all others; the second brother wants to have power over Death; and the youngest brother wants to leave Death safely behind him.

Eventually the brothers take their gifts and go their separate ways, toward very different fates. The first travels to a "certain village" and tracks down a wizard with whom he had fought to challenge him to a duel he "could not fail to win." After killing his enemy, he retires to an inn where he brags about the Elder wand, how he won it from "Death himself," and how it makes him all-powerful. That night, a wizard sneaks up on the oldest brother and steals the wand, slitting the brother's throat "for good measure." The haunting refrain, in which Rowling describes Death as taking the brother "for his own," helps both anchor the story as a cautionary tale as well as teach a lesson about the inevitability of death. One of the most important messages from this tale, and from this particular brother, is the notion of using power for good (advice Rowling clearly takes to heart).

The second brother arrives at his empty home, where he turns the stone "over thrice in his hand", using it to "recall the Dead" (capitalized in our copy). He is thrilled to witness the return of the girl he once wanted to marry, however she is "silent and cold" and suffering because she no longer belongs in the "mortal world." Desperate and filled with "hopeless longing" the second brother kills himself so that he can join her, allowing Death to win back his second victim.

The youngest brother uses the "Cloak of Invisibility" to hide from Death, until at "very old age" he takes it off and gives it to his son. Then, he greets Death "gladly" and "as an old friend" and departs from "this life." Such a satisfying close to this tale--it still packs a punch even after a second reading. Simple, powerful, and poignant, "The Tale of the Three Brothers" introduces theories about the use and abuse of power (also strong in the series) and shares important messages about life and death. There are many ways in which this tale informs and enhances Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows (the curious should reread Chapter Thirty-Five, "King’s Cross" and discuss), but our favorite is highlighted by the message that Dumbledore himself imparts to Harry about accepting Death and embracing life: "Do not pity the dead, Harry. Pity the living, and above all, those who live without love." The youngest brother did not try to cheat Death or harm others with his power; instead, he used his gift to live simply and without fear of Death, so that at the end of a long and happy life, he was able to go willingly from this world.

It is a true testament to Rowling’s talent that her fairy tales carry such a strong message, but never appear preachy or overtly didactic (this goes double for her books, and is in part why they are so special). The Tales of Beedle the Bard imparts several of the same lessons as the Harry Potter series, and the stories reverberate with Dumbledore's warning about choosing "what is right and what is easy." Whether she is warning against arrogance and greed, revealing the responsibilities that come with immense power, or extolling the importance of love and faith in oneself, Rowling's boundless imagination and masterful storytelling keep her loyal fans (young and old) coming back for more, ever eager for the next lesson.

No comments:

Post a Comment